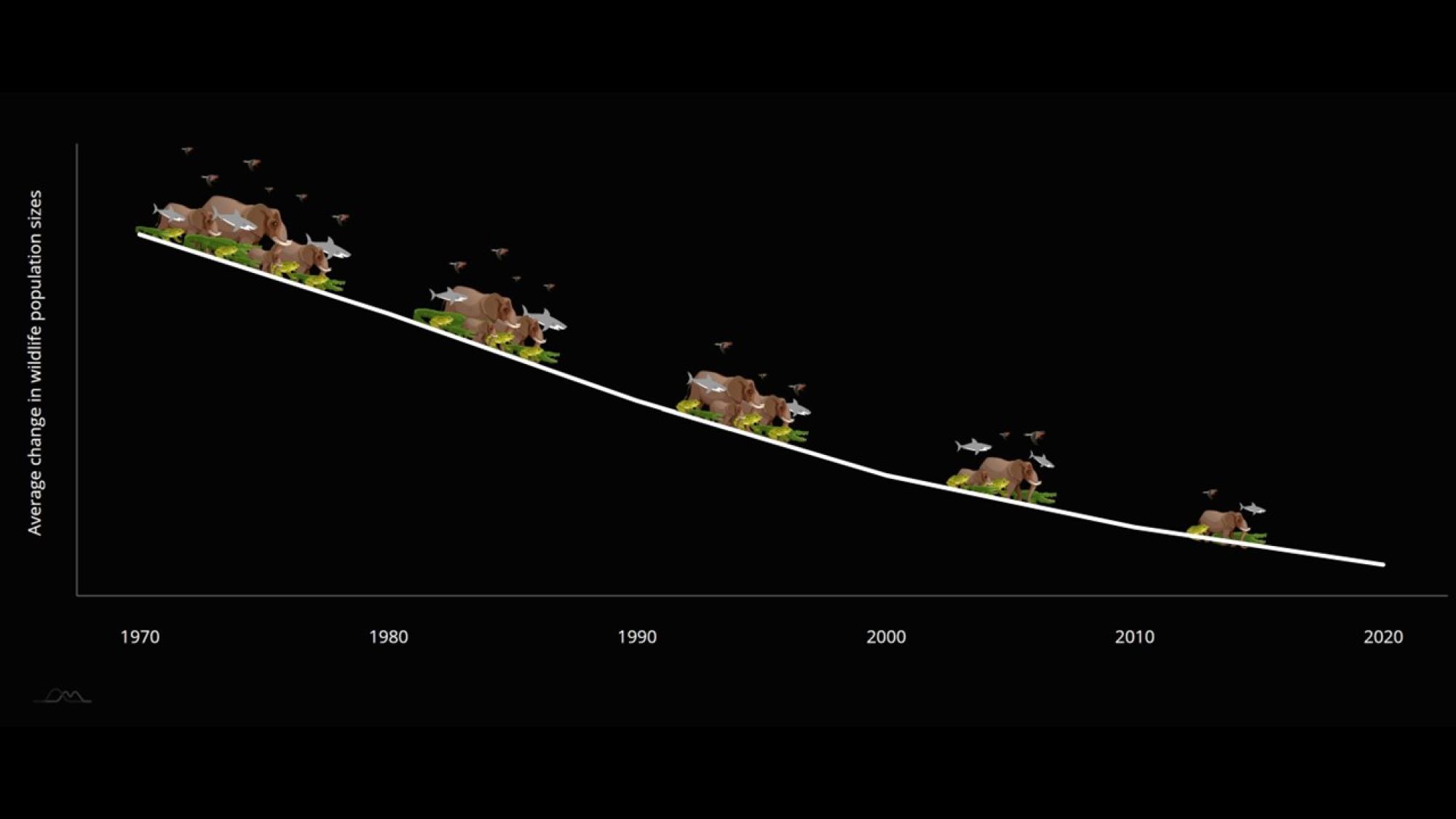

Exploring resilience

The Exploring resilience blog discusses the current themes of research, teaching and development of resilience, i.e., crisis resistance and deepens knowledge about the management of global change, and possible solutions to the wicked problems of sustainability. The authors are researchers and experts in the field, and members of the cooperation networks of the University of Oulu’s FRONT PROFI7 research programme.